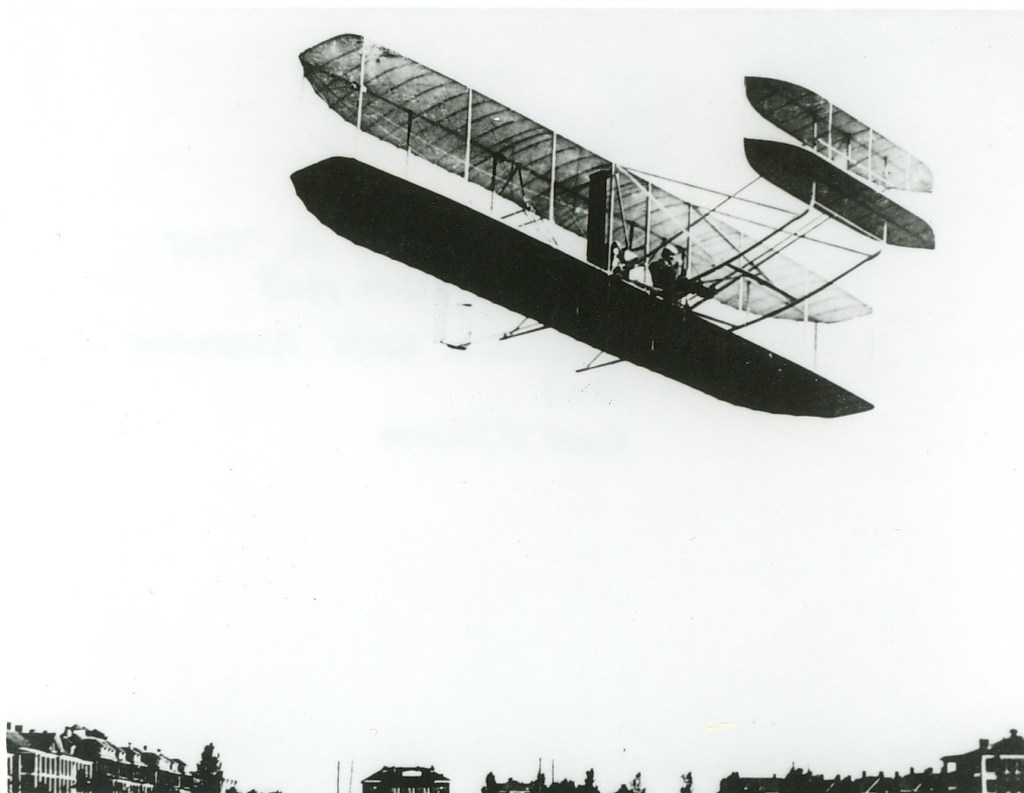

I don’t think that we truly realize just how far we have come in the past one-hundred-twenty-five years. By 1900, Wilbur and Orville Wright were already building the first airplane. Three years later, they took to the sky. It was a mere one-hundred-twenty foot, twelve second flight, but this flight was the most important in history.

The Wright Flyer and the Years Before World War One

The Wright Flyer is far removed from modern aircraft. In fact, the Wright Flyer is not closely related in design to the aircraft that flew in World War One. The Wright Flyer used a tiny, one-hundred-eighty pound engine producing twelve horsepower. The propellers were held in place by bicycle frames, and the engine was connected by a bicycle chain. The pitch control surfaces were placed on the front of the aircraft, rather than the now traditional tail mount. Most interestingly, the Wright Flyer did not use any flaps or ailerons to roll the plane. Instead, the Wright Brothers used a system called wing warping. In this method, the entire wing would move and twist to deflect air. At the low speeds the Wright Flyer flew at, and because of the thin, flexible nature of these wings, wing warping created less drag and allowed greater control.

It wouldn’t be long until the military saw the possibilities for the application of aircraft in warfare. In 1909, the U.S. Army took its first flight with their own aircraft.

Other countries quickly began building their own aircraft, and even adopting them into service. These aircraft were not fitted with weapons, but could be used in scouting roles. While the first British military aircraft greatly resembled the Signal Corps No. 1, French and German designs differed significantly.

Early Uses of Aircraft in War

Even before World War One began, aircraft were beginning to be used in combat. While not one plane against another, the first bomb was dropped from an aircraft by Giulio Gavotti from a Etrich Taube in 1911, during the Italian-Turkish War in Libya.

By the time the first World War broke out, planes had evolved. While many still used wing warping for flight, others were adopting ailerons. Ailerons, though causing more drag when deflected, allowed an aircraft to use stronger, thicker wings and to fly at high speeds. More importantly, aircraft engines had improved significantly. Larger, more complex engines were being used, meaning aircraft could fly higher and faster.

Still, the basic principals of flight were poorly understood. Around half of all pilot fatalities occurred from training and non-combat crashes. Forces of flight, well understood today, were unknown. This not only made for less safe piloting, but also for less stable aircraft.

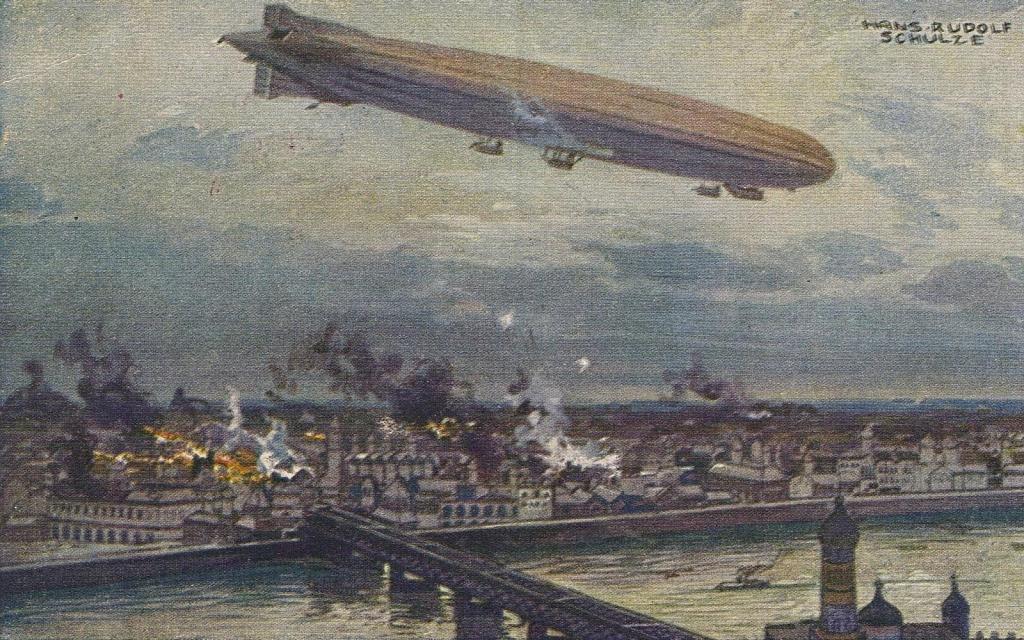

In the beginning of the war, aircraft were not being used for combat. Rather, they were reconnaissance vehicles. In the trench warfare world of the first World War, this was massive. Zeppelins were already being used for aerial photography, aerial gunnery, and strategic bombing.

Aircraft were able to complete aerial reconnaissance very effectively. Their small, quick nature was able to survey battlefields and quickly report back to commanding officers. In 1914, reconnaissance aircraft were able to halt the German invasion of France.

This would all change shortly after.

Combat and War

Aviators on opposing sides were generally kind to each other early in the war. Stories of friendly waves exchanged between “enemy” pilots were common. One day, though, pilots and their rear seaters drew their guns and fired at another aircraft. After that, things would never be the same.

Soon, pilots were mounting machine guns to their aircraft to allow them to fly and shoot at the same time. The most obvious area for guns would be the nose. Some pilots were mounting automatic guns on the tops of the wings, but the lack of crosshairs made aiming difficult. Nose mounted guns had one issue, though: the propeller.

There was already a solution for this.

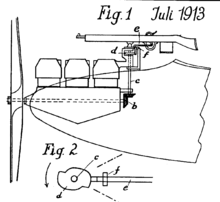

In 1913, Franz Schneider patented a synchronizer while working for L.V.G. in Germany. While previously working for Nieuport, he had since left the French company and started working for Germany.

The synchronizer linked with the propeller of the aircraft to ensure that it only fired between the propeller blades as they spun. Many countries quickly adopted this new technology as it began to hit the combat scene. The first aircraft to adopt this technology was the Fokker Eindecker, and many countries followed suit.

As the war progressed, aircraft became more and more sophisticated in their designs. Biplanes began to dominate the battlefield; their extra lift allowed for slower maneuvering and less likely stalls. Still, most aircraft had no throttles, few instruments, and were severely underpowered. The British, French, and German aircraft were in a constant arms race to get ahead of one another.

Engagements

Dogfighting was in its infancy, and the art of engagements was shaky. Many fights ended not because another aircraft was “shot down,” but because an aircraft lost control and spun into the ground. Others would end in collisions. In fights where shots were on target, pilots would see their enemies maimed and bleeding only feet from each other.

There was something knightly, almost chivalrous, about these fights. The daring attitudes of many pilots inspired others to join, and painted a mystical image of the fighter ace. While most of these young men succumbed to early graves, many made names of themselves that live on to this day. Baron von Richthofen, also known as The Red Baron, shot down over eighty allied aircraft. He was only twenty-five years old when he was killed.

Impacts

Following World War One, the world would never be the same. The weapons and tactics of war had shifted, and aircraft were becoming accepted as a mainstay in worldwide technology. While many countries saw the end of this war to be the end of all wars, aircraft continued to be adopted and advanced in many uses. Over were the days of adventurous dogfighting between pioneers of the sky.

The next entry in this blog will cover the interwar period of aircraft advancement: a time of tremendous change.

Leave a comment